The Disney Animator's Strike Part 2: How It Led To The Blacklist

The Road To The Blacklist Started With The Disney Strike, but it is not what you've been told.

You probably know what the Hollywood blacklist was, although it lasted less than a decade and ended more than sixty years ago. It’s legendary; you have to at least heard of it. It’s one of the central events of the Crucifixion pageant of the American Left, remembered as a senseless random political purge of all our most talented writers, the Hollywood Ten. The punishment that Joe McCarthy and the American Right shoved down Hollywood’s throat for the sins of being for civil rights and world peace. These people were never Communists, and so what if they were? A generation of idealistic Hollywood acting and writing talent, working so industriously for years within the studio system, went down the drain, hauled off to jail, driving cabs and pumping gas instead of creating the healing works America so badly needed and so badly lacked in our backward, frightening postwar era.

That’s the legend, widely accepted for more than half a century as the truth. Yet, at the time, even the people most directly involved knew better. People called it McCarthyism, but the Hollywood blacklist had nothing to do with Joe McCarthy. Few of the blacklisted writers stayed unemployed for long, and some were lionized for the rest of their lives. The Republicans and the Right had very little to do with the blacklist. Above all, it was a frantic attempt on the part of liberals to save their own skins with the moviegoing public by tossing their friends and former allies out. Twenty years ago, Academy Award nominee Lionel Chetwynd, the conservative director and screenwriter, gave me a clue to what I’d find when I looked at the subject closely. “The secret of the blacklist? It was something Hollywood did to itself, but we’ve successfully managed to blame everyone else.”

So how did the spurious legend become accepted? It blurs together personalities, reverses cause and effect, mixes up the true sequence of events, and keeps shifting perspective to artfully misdirect our attention away from the main action at key moments. That’s what a good Hollywood editor does. In one sense, the daily “rushes” (the latest photographed scenes, fresh back from the lab) of any movie are also a documentary on what happened on the set yesterday. It’s the editor who makes them into a fictional story. And this one is one big fiction. Scrap the edited version they want you to play in your head when you hear the words “Hollywood blacklist.” Let’s thread up the original, uncut rushes on the Moviola.

V.J.Jerome, cultural chief of the Communist Party, was one of the prewar architects of a pincer movement to gain influence in Hollywood; the backbone would be a takeover of studio unions, the brains would be the screenwriters. Quite a number of early Forties films praised the Soviets for their fight with Hitler, but at the time party leadership counseled stealthier methods of getting progressive material into scripts. During the war, the Communist Party USA supported a no-strike policy of temporary labor peace at a time when the USSR was still in danger. By March 1945, with victory in Europe only weeks away, the semi-truce with capitalism was over. The head of the Party, Earl Browder, would even lose his job over his alleged collaborationist policies.

The time seemed right for a big strike. Herb Sorrell, head of the Communist-led Conference of Studio Unions, was urged by ally Harry Bridges of San Francisco’s Longshoremen’s Union to get more aggressive with his powerful Hollywood opponents, IATSE, the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees, the oldest and largest union in American show business. IATSE had 77,000 members nationwide compared to CSU’s 10,000, but the numbers were closer in Hollywood alone, 18,000 IA to roughly 8,000 CSU.

Despite that, Herb Sorrell enjoyed some advantages in a jurisdictional turf war with the IA. Sorrell claimed a David-versus-Goliath angle to explain that large imbalance in support. It had been about five years since IATSE kicked out some of the most vicious Mob-connected gangsters in the history of the American labor movement. Instead of respect for their courage, the new “clean” IA leadership got nothing but insults from the press, who treated them like they were still the mobsters of the Thirties. The main reason for that was a widespread bias in favor of their “idealistic” competition of the hard Left. This was also a time when our wartime allies, the Soviets, were riding higher in US prestige than ever before or since.

The IA’s new special business agent in Hollywood, Roy Brewer, was a Nebraskan projectionist whose work in national union leadership was essential in cleaning it up. He’d survived a lot before he ever got to Hollywood. If CSU was muscling in on IATSE, trying to get them decertified and their members locked out—basically, tossed out of the film industry—then Brewer would counterattack with everything he had. At first he was ignored, then ridiculed. He was relentlessly second-guessed by restless IA locals, some of them with a remaining mob tinge or Red leanings, and had to get them in line. Many of the CSU’s member unions and many of their members were once in IATSE before the gangster days and were potentially open to rejoining it. Some of those members spoke freely to their IA friends. One of the few semi-comic episodes in this grim struggle was The Battle of the Microphones, an ill-advised CSU attempt to bug Roy Brewer’s office, which he got wind of. Tactically this was a dumb move. Brewer had the world’s best soundmen at his disposal, “borrowing” the studios’ most sensitive equipment. It is said that CSU meetings provided some of the finest surveillance recordings ever made.

Although many CSU craft locals were ostensibly affiliated with the AFL, American Federation of Labor, the AFL disavowed the Hollywood strike and urged a peaceful end to the labor war. They were ignored. CSU’s enthusiastic supporters included the newer, left-dominated CIO, (Congress of Industrial Organizations), the Screen Actors Guild and its charismatic leader, Ronald Reagan, the screenwriters, the journalists of Variety, the daily newspaper of the film industry, and even, incredibly, the Archdiocese of Los Angeles, convinced of CSU’s virtue by Father George Dunne, a “labor priest” at Loyola Marymount University. Basking in his good guy image in the first months of the strike, Party member Herb Sorrell decided to radically intensify this labor-against-labor offensive, with the goal of the CSU forcibly taking over IATSE’s Hollywood production locals, pushing for dominance by shutting the studios down completely, something that not even the prewar mobsters could have done. At first, they succeeded beyond their wildest dreams.

At dawn on October 5, 1945, at the gates of the Warner Brothers studio, more than a thousand people showed up to begin the most famous labor action in film history, the Battle of Burbank. As one of today’s flashmobs, the new CSU tactic was to surprise, to swarm and intimidate with an overwhelming number of pickets and, soon enough, rioters, showing up unannounced. They breached the Warners gate and vandalized the lot, affecting production for weeks. Starting the next day they fanned out.

In what was then a century of labor history, no previous generations of laborers were able to find out about strike locations on local radio, or drive themselves to the picket line in Mercury V-8s. The tiny police forces of sleepy Burbank (Warners), as well as distant West Los Angeles (20th Century Fox) and little Culver City (Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer and Selznick), were unprepared and outmanned by the new technique of labor flying squads. You can’t blame the cops; everyone but the CSU was shocked. The far larger LAPD, led by rough men in a rough era, were somewhat better equipped to handle action against Columbia, Paramount, and RKO, but even they were sporadically unable to keep the studio gates open. Pictures of the violence on the picket lines were on front pages and in newsreels everywhere.

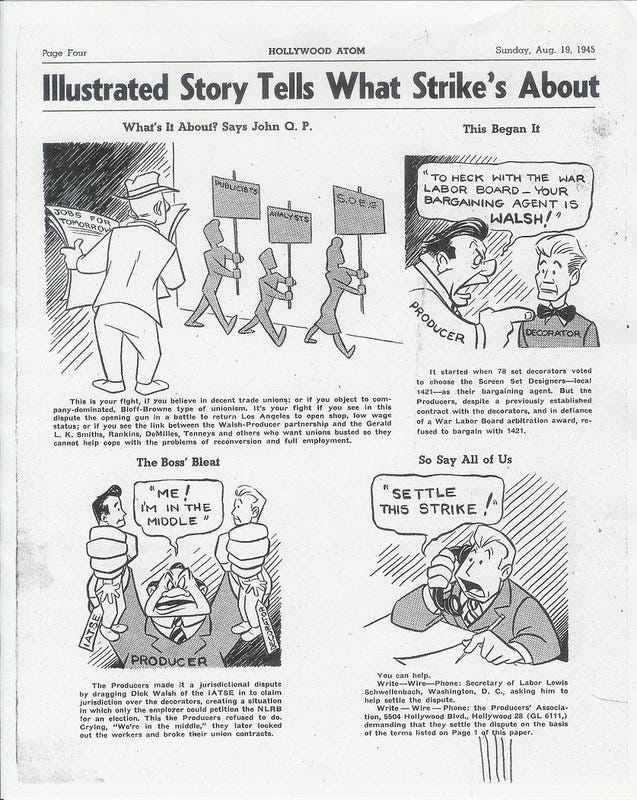

This wasn’t Dearborn or Detroit. Hollywood had seen a nasty, unpleasant fight at Disney in 1941, but nothing remotely on the scale of this new postwar ultraviolence, with dozens of cars overturned, non-strikers splashed with gasoline, and home-phoned death threats. Lloyd Billingsley quotes Kirk Douglas: “Thousands of people fought in the middle of Barham Boulevard with knives, clubs, battery cables, brass knuckles, and chains.” Screenwriter Dalton Trumbo, soon to be a member of that famous Hollywood Ten, smirked about the violence, and gave a quote to the CSU’s strike newspaper, Hollywood Atom: “A car becomes a lethal weapon when its obvious purpose is to clear a path over the bodies of pedestrians. What can you do to defend yourself but turn it over?”, said the future two-time Oscar winner.

Film production nearly ground to a halt, just as Herb Sorrell had promised. At least in their day, the chiefs at Ford and General Motors had sufficient warning to build a war chest. The once-oblivious studio bosses, living close to the financial edge as always, were dependent on steady cash flow, as Sorrell’s strategists calculated. He counted on their desperation to resume production. But the CSU’s real price, they finally knew by now, was nothing less than effective control of the studios, to be followed someday by actual ownership.

That desperation instead led the studios to deal even further with CSU’s mortal enemies, IATSE, a fateful strategic error on Herb Sorrell’s part. As the IA began to win over the minority of craft workers it didn’t already represent, Roy Brewer was despised and defamed in the fashionable press. It’s important to remember that throughout the course of this story, this prominent anti-Communist labor leader was a Democrat, a New Dealer, and by the standards of his day, a liberal. In retrospect, it makes his treatment by the press more shocking.

The 1945 strikes were wrestled to an uneasy truce in December by intensive industry negotiation. The studios stuck with IATSE and the Teamsters. Brewer pocketed IATSE’s gains, but nobody thought CSU would accept a lasting peace, and soon they would go back on their word and turn out the picket lines again.

The violence and scale of the strikes put off some of CSU’s friends. Even the staunchest ones, like the Screen Actors Guild, were clear that they didn’t want another work stoppage in 1946. The screenwriters, who since the Thirties had boasted of their association with studio labor, realized that this less and less popular alliance with blood in the streets was starting to bring unwanted and potentially hazardous public attention to their own political work. Leftist writers feared and resented the discipline of the harder postwar Party line. Popular members like producer Adrian Scott and writer-director Edward Dmytryk were expelled to make examples of them; others, like Albert Maltz, were forced to make humiliating “confessions” in Party publications and public meetings.

Herb Sorrell’s labor tactics would at first be just as public, just as violent, but as the September 1946 strike season began again, Sorrell quickly discovered the script had to be a little different this time; more carefully targeted, aimed at shutting down production mostly away from the studio gates, where displays of raw muscle power, arson, and assault tended to scare off their newly ambivalent allies.

In October, they struck Technicolor laboratories with an unusual focus on what was normally a quiet, overlooked industrial part of the film business, just as they were gearing up to make hundreds of copies of the year’s most expensive Christmastime releases. This was a shrewd and cynical move, as at the time the company had a virtual patent monopoly over color film production for every studio in Hollywood. Film processing of studio dailies was also disrupted, so every color film in town that was still shooting, many trying to make that critical Christmas deadline, stopped as well. At the gates of Technicolor, Sorrell had the eager help of out of town thugs supplied by Party allies, like the Longshoremen. But Roy Brewer’s men, already hardened by internal combat with the Mafia, were still able to make common cause with old buddies in the Teamsters Union. IATSE retook legal control of the laboratory worker’s union, kicked out the CSU, and sound stages all over town went back to work.

Now it was an even fight, and for the first time Sorrell and the CSU were clearly, publicly losing. They were as stunned by this turn of events, this reversal of fortune as their enemies the studio bosses had been a year ago.

For nearly two years, the actors had gone along with whatever the unions wanted, and by the unions, they meant the minority of workers who were in CSU locals, as if the far more numerous IATSE and Teamsters who actually worked on their sets didn’t really count. The formerly rough IA had conducted itself honestly and would keep production going. SAG’s official allies, CSU, had proven themselves deceitful and erratic. Many now suspected that ideology was pulling the strings, at a higher political level than Herb Sorrell.

The tide was beginning to shift. Many disillusioned actors began moving away from supporting the CSU. At a critical public labor meeting at Hollywood’s Hotel Knickerbocker on October 24, 1946, SAG had had enough. “Herb, as far as I am concerned, you have shown tonight that you intend to welsh on your statement of two nights ago, and as far as I am concerned you do not want peace in the motion picture industry.” Ronald Reagan got a storm of applause.

On January 19, 1947, CSU released what they considered their definitive statement on the question, “What Is the Role of Communists in the Hollywood Unions?”, evading the question while refusing to retreat. “Are there Communists in Hollywood unions? Communism is a working-class movement. So it is natural to find them in trade unions. Do Communists want to dominate the industry for propaganda? No. The producers try to evade the real issue of signed contracts for their workers by raising the phony issue of Red Control…The fight of the labor movement for its just demands, important as it is, can but partially solve the problems of the working class. The Marxist theory of Scientific Socialism provides the answer…” At this point, even their more stubborn non-Communist allies, like Gene Kelly and Jimmy Cagney, pulled away from active support of Herb Sorrell and his Conference of Studio Unions.

For two years, the hard left organizers of the industry-wide strikes were overjoyed when newsreels of the violence in the streets of Hollywood startled worldwide audiences, winning praise and support from European and Soviet writers. There was never anything accidental about the choice of this photogenic target, visual proof that even in the heart of the capitalist dream factory, politically aware film workers were in rebellion against club-wielding police, fighting for their rights like starving Okies and Arkies in the Depression-era fields.

But the Communist Party overplayed its hand. Telephoto close-ups of fist fights on Cahuenga Avenue thrilled them in Kharkov and Nizhny Novgorod, but by the beginning of 1947, Hollywood’s influential writers and directors were, by and large, horrified with the length and irrationality of the work stoppages.

This wasn’t the sensible, pro-worker action program Herb Sorrell and a dozen coalition, peace and front groups allied with CSU had promised them in the final years of the war. The movie unions were once supposed to be the tame petting zoo that bore living witness to the progressive ideas the writers put on screen. Instead, actual Party members were demonstrating internal discipline, readiness to lie and to resort to violence that greatly exceeded even that of the socially-not-conscious labor mobsters of the Thirties.

The strikes played particularly badly with the American public, who were shocked by the thuggish scenes in newspapers, magazines and on screen. The newsreels did not, as CSU hoped, inspire millions of (pre-TV) Americans to give up moviegoing for a few months until the studios could be strangled into submission. Quite the opposite. Waves of postwar strikes in strategic industries—coal, cars, railroads, steel, electricity, glass, cement–squandered much of the goodwill that unions had built over the Depression years with non-members. Partly as a result, the 1946 elections repudiated the New Deal, putting Republicans in control of the House and Senate for the first time since Calvin Coolidge was president.

Since before the end of the war, Herb Sorrell’s CSU did everything humanly possible to attract the attention of legislators in Washington, and in 1947 they were about to get it, with all the reporters, microphones and flood lamps they could desire. Ooh, were they gonna get it.

By Gary McVey

Coming: Part 3 You will never guess who started the blacklist!

Behind the paywall: Resolved: The Hollywood Reds did more Harm than Good.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Hidden Cold War History to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.