THE ATOMIC CAFE: The film that exposes the deadliest secret of the atomic age

Truman decided to hide the effects of radiation from the public and THE ATOMIC CAFE now documents the absurdity - and horror, of that denial.

When the first footage shot in Japan after the atomic bombs were dropped on it were seen the films were quickly classified. The effects of radiation were hidden from the world (as was the fact Japan had been trying to surrender for a year before the bombs were dropped).

This would lead to surreal and monstrous uses of radiation which everyone was told was safe (just as the world had been told Hiroshima and Nagasaki were military targets and not civilian areas).

Radioactive materials were used in make-up, to make glow in the dark watches, on plates for eating.

Soldiers were marched into areas where nuclear blasts had occurred without realizing the danger they were being exposed to.

When those soldiers became ill, they were denied help from insurance companies because the government would say for years radiation was safe.

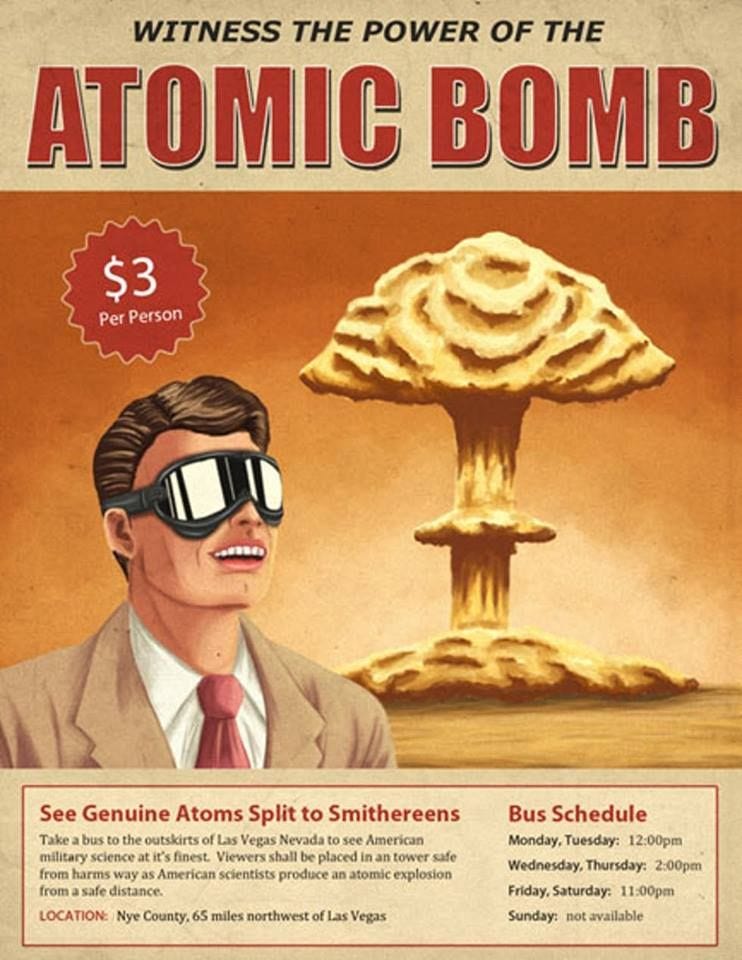

What do Presidents Truman, Eisenhower Kennedy and LBJ have in common all have in common? They decided it was best the American public not know the true danger of radiation. After "tests" occurred near major cities people were told to put salt in their bath and all would be well. The government produced large numbers of films aimed at reassuring people that even atomic bombs could be survivable- if one just ducked and covered.

These films linger on in the documentary ATOMIC CAFE, which is both funny and tragic. The film was produced over a five-year period through the collaborative efforts of three directors: Jayne Loader, and brothers Kevin and Pierce Rafferty. For this film, the Rafferty brothers and Loader formed the production company "Archives Project Inc." The filmmakers opted not to use narration, and instead they deployed carefully constructed sequences of film clips to make their points. Jayne Loader has referred to The Atomic Cafe as a compilation verite, meaning that it is a compilation film with no "Voice of God" narration and no new footage added by the filmmakers. The soundtrack utilizes atomic-themed songs from the Cold War era to underscore the themes of the film.

It remains a powerful, sometimes funny, sometimes horrific documentary:

Mainstream American conservatives—not leftists, as we are led to believe—have been among the most vocal critics of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. At the time, they didn't know Japan had been trying to surrender for a year, but they still condemned the bombing. Consider the following:

On August 8, 1945, two days after the bombing, former Republican President Herbert Hoover wrote to a friend that "[t]he use of the atomic bomb, with its indiscriminate killing of women and children, revolts my soul."

Days later, David Lawrence, the conservative owner and editor of U.S. News (now U.S. News & World Report), argued that Japan's surrender had been inevitable without the atomic bomb. He added that justifications of "military necessity" will "never erase from our minds the simple truth that we, of all civilized nations . . . did not hesitate to employ the most destructive weapon of all times indiscriminately against men, women and children."

Just weeks after Japan's surrender, an article published in the conservative magazine Human Events, contended that America's atomic destruction of Hiroshima might be morally "more shameful" and "more degrading" than Japan's "indefensible and infamous act of aggression" at Pearl Harbor.

Such scathing criticism on the part of leading American conservatives continued well after 1945. A 1947 editorial in the Chicago Tribune, at the time a leading conservative voice, claimed that President Truman and his advisers were guilty of "crimes against humanity" for "the utterly unnecessary killing of uncounted Japanese."

In 1948, Henry Luce, the conservative owner of Time, Life, and Fortune, stated that "[i]f, instead of our doctrine of 'unconditional surrender,' we had all along made our conditions clear, I have little doubt that the war with Japan would have ended soon without the bomb explosion which so jarred the Christian conscience."

A steady drumbeat of conservative criticism continued throughout the 1950s. A 1958 editorial in William F. Buckley, Jr.'s National Review took former President Truman to task for his then-current explanation of why he had decided to drop an atomic bomb on the city of Hiroshima. The editors asked the question that "ought to haunt Harry Truman: 'Was it really necessary?' " Could a demonstration of the bomb and an ultimatum have ended the war? The editors challenged Truman to provide a satisfactory answer. Six weeks later the magazine published an article harshly critical of Truman's atomic bomb decision.

Two years later, David Lawrence informed his magazine's readers that it was "not too late to confess our guilt and to ask God and all the world to forgive our error" of having used atomic weapons against civilians. As a 1959 National Review article matter-of-factly stated: "The indefensibility of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima is becoming a part of the national conservative creed."