SPECIAL REPORT! The Disney Animator's Strike Of 1941 #1

Historians, labor unions and people who hate Walt Disney have dominated the story of the strike. Now it's time for the truth.

UNDER THE TUTELAGE OF HARRY BRIDGES

Herb Sorrell had learned about strikes when he worked under Harry Bridges, the head of the West Coast Longshoremen's Union. Harry was identified as a Communist Party member in hearings that took place in 1941. But here's the part of the story everyone leaves out, the period Sorrell worked with Bridges was during the Hitler - Stalin Peace Pact. From 1938 to the end of June 1941 Communist Party members around the world praised Hitler and his new form of socialism. During this period, we had wild cat and crippling strikes that were organized by Communists and German American Bund members working together

to stop what they called the imperialist war mongers, FDR and Churchill.

The abrupt change from hating Hitler to praising him actually led to some members quitting, but those numbers are hard to come by. There was no discussion of the abrupt change, members were expected to follow the party line.

The West Coast Longshoremen did their part by smuggling Nazi propaganda into the U.S., the violent and disruptive strike that Disney strike leader Harry Sorrell and Bridges worked on together was secretly funded by the CPUSA (Communist Party USA). How do we know this? Sorrell bragged about it to anyone who would listen.

EX-RED GUARD NAMES BRIDGES

To this day pro-Stalinists claim Disney was delusional about Communists leading the strike. But there was a court case, and Disney was proven correct.

A former guard at local Communist Party headquarters, Richard St. Clair, testified that Harry Bridges conferred there several times with local party leaders and longshore officials. Mr. St. Clair said other Communists told him: “Yes, Bridges is one of us, but keep your mouth shut about it.”

The CPUSA had both public and secret members during this time.

Defense attorneys, during cross-examination, brought out that while Mr. Wilmot was editing the Labor New Dealer, a Portland publication, he was also employed on a WPA writers’ project. Mr. Wilmot declared, however, that “as I was a non-certified WPA worker it was all right for me to do outside work.

Telling of what he described as a “top fraction” Communist meeting in Portland in April, 1938, Mr. Wilmot said he went to a hotel room and met Mr. Bridges, but left almost immediately after stating that “Jo-Jo will tell the boys, what to do.

Jo-Jo was identified as Joe Ring, “a Communist and Bridges’ bodyguard.

During the meeting, said Mr. Wilmot, Mr. Bridges’ desire for the removal of John Brost, an assistant regional CIO director in Oregon, was discussed.

‘I’d Do as I was Told’

“The committee decided I should take Brost’s job,” said Mr. Wilmot. “I protested, but Jo-Jo told me I’d do as I was told.” At another meeting, attended by Mr. Bridges, Mr. Wilmot was on the carpet for the manner in which he was editing The Labor New Dealer, he said. He quoted Harry Pilcher, a Communist, as saying to Mr. Bridges:

“Bob (Mr. Wilmot) doesn’t always follow the party line.”Mr. Bridges commented, according to the witness:

“We Communists have to stick together.”Mr. Wilmot testified he had been fighting the Communist Party and had refused to run party statements in the paper.“

Bridges said I should run those statement,” he testified. “Bridges said that if I behaved myself I might come down to San Francisco and ‘get a job on a good paper’.

Defense attorneys asked:

“What is your personal opinion of Harry Bridges?”

I believe him to be the greatest enemy the labor movement has,” replied Mr. Wilmot.

He said that when he first came from the East he considered Mr. Bridges a great labor leader, but later changed his mind.

Later on, on redirect examination, Mr. Wilmot said:

“I consider him too dictatorial, and I resent attempts to frame people who don’t agree with him. I just don’t like him.”

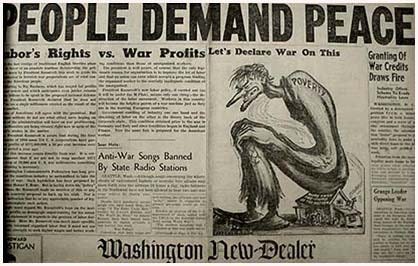

The above Communist newspaper is something every Hollywood Exec, historian and progressive prays you never see. This was when the Communist Party USA supported Hitler and called Churchill and FDR imperialists and war mongers.

Why Disney?

The Washington New Dealer was a communist newspaper that followed the Comintern line of the moment. I write of the moment as it was expected to follow Stalin's beliefs without criticism and when Sorrell worked with Bridges that political line was to stop FDR from fighting Hitler. The Comintern were 80 Communist parties worldwide all controlled by Stalin, these parties had put aside the problems their nations had to support the Soviet Union. During this time Dalton Trumbo wrote the anti- war novel JOHNNY GOT HIS GUN - a book immediately removed from print when Stalin ordered all communists to encourage FDR to enter the war against Hitler.

When the Hitler - Stalin Peace Pact happened and communists supported Hitler, France had been invaded and England was being bombed. Pete Seeger actually joined the party when it supported Hitler. This was when Sorrell worked with Communist Party member Harry Bridges and bragged that the strike had been financed by the Communist Party.

QUOTE:

“The Disney Version” (1968), film critic Richard Schickel’s muckraking history that came out about a year after Walt Disney died. I didn’t like it. At a time when show business biographies were usually positive, in Richard Schickel’s view, Disney, for decades one of the most admired men in America, had to be debunked as a hard core right winger, a mean boss and anti-Semite who threw away his early creativity for the sake of fatter and fatter profits. Although the book didn’t really resonate much with the wider public, who still loved Walt, it was a shock that hurt the Disney family deeply and it would remain the intellectual standard version, the highbrow’s favorite definitive reference work on the subject of Walt Disney for nearly thirty years.

The Disney strike all but defined “Pyrrhic victory” for Forties Hollywood. The hard left rejoiced because in the short term they “won”. But in the end everyone lost. The actual workers involved rued the day they ever got tricked into a strike. Employment was cut in half. Disney management, unusually solicitous of their employees before the strike, became rule-driven time clock watchers afterwards. And Walt Disney himself, until then a political blank, was transformed by the nine-week strike into a fierce anti-Communist crusader. He was convinced right to the last days of his life that Hollywood’s hard left used illicit, immoral, and sometimes cruel methods to try to seize control of the workforce of his studio. He wasn’t wrong.

It’s the strike that by the Seventies, nobody but former radicals like Jules Engel seemed to want to own up to having supported. So how did it happen?

Herb Sorrell, the Communist Party’s key man in the Hollywood labor movement. His heavily politicized “service” organization, the Conference of Studio Unions, (CSU) was a ragtag group of small craft unions that weren’t part of IATSE, the dominant show business labor organization from coast to coast. The IA had been a Mob-invaded union that kicked out the gangsters in the beginning of the Forties. Now IA’s biggest strategic problem wasn’t the studio chiefs and theater chain bosses, but well funded competition on the far left.

Sorrell’s left wing of the left wing of the labor movement could only get at bits and pieces of the film industry (his political siblings in the screenwriting suites were doing somewhat better), but one sub-branch of Hollywood that proved to be surprisingly easy pickings was cartooning. His pickets, his pressure groups, and his friends in some corners of the press resulted in his signing up most of Hollywood’s smaller animation studios, starting with the little guys, the Flip the Frogs and Farmer Alfalfas who had no resources to fall back on. Sorrell’s CSU kept moving up the scale. Woody Woodpecker, Tom and Jerry, and Popeye the Sailor were all produced in closed shops now; you had to join the union or you couldn’t work.

Finally they forced their second-biggest target, Warner Bros. into a contract. Ironically, Warners had the most left wing content in Hollywood, but they had to be dragged kicking and screaming to the bargaining table. Porky, Daffy and Bugs carried union cards now. When Warners animation boss Leon Schlesinger signed that deal, he asked one querulous question, quoted in Variety, that echoed ominously through the industry: “What about Disney?” he whined plaintively. It showed a certain lack of solidarity among the showbiz boss class, you might say.

And indeed, Disney was by far the toughest target in Hollywood for forced labor recruitment: it had the best pay, working conditions, artistic tools, and sense of making magic in the entire animation industry. If there was anyplace in the American workforce where paternalism seemed to work wonders, it was Walt Disney Studios. There’s a great book that I highly recommend, Mindy Johnson’s “Ink and Paint: The Women of Walt Disney’s Animation”, a so-called coffee table book that’s about as thick and heavy as your coffee table. It’s $40 on Amazon and well worth it, with the most beautiful color printing imaginable of nearly a century of Disney art, proudly presented by some of the women who helped make it. “Ink and Paint” is one of the best visual histories of classic era Hollywood around. It tells a fascinating technical story about the evolution of animation that’s also a warmly human one. Accustomed to other books about women in Hollywood history, you read it waiting for a modern feminist hammer to drop. But it never does, not in today’s terms. The women at Disney thought they were incredibly lucky to have been there while history was made, and for having been on the team.

Photo: Harry Bridges who at the same time as the strike was promoting the Hitler-Stalin Peace Pact

The book’s descriptions of the step by step process of making cartoons begins to explain a little of why the animation business found it unusually hard to resist union organizing efforts. Unlike capital-intensive regular moviemaking, with its sets and costumes, its elaborate lighting, camera, and sound crews and its costly equipment, an animation studio needs little more than desks and paper. It is enormously labor intensive, more so than any other branch of filmmaking. As a result, it is also more regimented: ten master animators set up scenes for dozens of rising young pros. Hundreds of assistants and “in-betweeners” filled in less vital drawings, constantly learning their craft. The mounting stacks of paper were continually sent to the animation camera, a vital but unglamorous job, often done in a basement, that resembled making blueprints or photocopies more than it did a movie studio.

These were “pencil tests”–shots that were completed in movement and drawing but not yet traced in and colored–submitted for Walt’s excruciatingly perfectionist inspection during daily screenings in the aptly named “sweatbox”. It was the boss’s top men, the chief animators, not the studio’s less exalted staff, who had to sweat. Once your fifth or fifteenth attempt to get it right passed muster with Disney, the drawings were sent to between sixty and three hundred women in the Ink and Paint Department to be finished to perfection before final filming.

Walt Disney’s role was similar to what Steve Jobs would become in our day; a merciless in-house critic who continually pushed for improvement. Unlike Jobs, Disney wasn’t a screamer or a bully. In fact, if you were a typist in Disney’s office, trimmed the hedges, or worked in the carpentry shop, “Walt” (no one was allowed to call him “Mr. Disney”) was fondly remembered as basically the kindly uncle we all later saw on television. But to his top animation talent, he wasn’t so nice. He felt, with some justification, that he’d made them what they were, and was not shy about letting them know that. As the company got bigger, he was sometimes capricious and petty about rewarding and penalizing them, a sure cue for resentment. They put up with it, of course; there was a Depression on, jobs were scarce, and hey, this was after all Walt Disney. But by 1941 the Depression had largely faded. Disney’s training was so good that his best animators could now have the pick of the best paying cartoon jobs anywhere else. Maybe they didn’t need uncle Walt bossing them around as much as they thought.

Other resentments were expertly played on. Disney custom built its new and permanent home, a veritable wonder city of animation. Then, just after everyone moved to the fancy new cartoon factory in Burbank, there was a brief wave of layoffs and pay cuts. The workers saw the massive new buildings, symbols of Disney’s fame and wealth but they didn’t see the massive new mortgage. They were also unaware, for example, that the spacious double-wide corridors and strangely oversized elevators were required by Disney’s bankers, who wanted their risky loan able to be quickly turned into a salable hospital in case of loan default.

The workers didn’t see that WWII had cut off Disney’s lucrative overseas markets. “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs” (1937), the first animated feature film, had been an enormous worldwide success. Its followup, “Pinocchio” (1939) was widely admired but not as widely seen; by the time it was ready for Europe, Europe was a lost market. By then, the next feature, “Fantasia” (1940) was already in the pipeline. With a two year lead time, its background in European classical music was designed from the beginning to be international in appeal, and the loss of overseas hit it particularly hard. Lower income was squeezing Disney tight, just as he was trying to pay his construction bills. Layoffs had always been a familiar part of working in films, but Disney had been largely immune the past few years. Fairly soon, hiring resumed.

Storyboards for “Dumbo”, a new, lower cost feature were in place, ready for animation to meet a Christmas 1941 deadline. Disney did what he always did; he spent every penny he had, and plenty that he didn’t have, to hire and re-hire all the animators he could, to the eternal despair of the company’s business manager, his brother Roy. To Walt Disney, the greatest service he could offer his workforce was the prospect of more work.

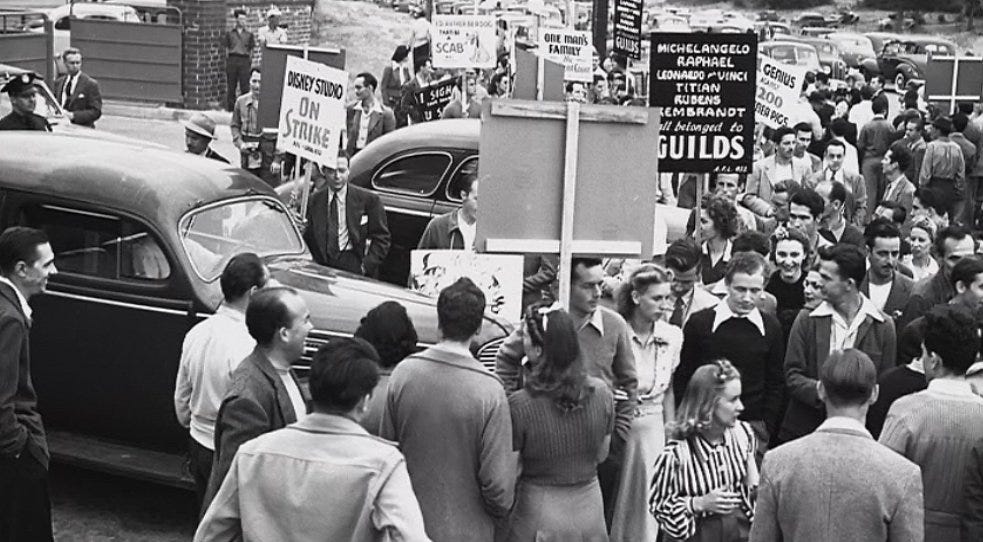

Earlier attempts at unionization had been voted down by longtime Disney employees, with the large, all-woman Ink and Paint Department as Walt’s strongest loyalists, as they saw themselves. Now, by hiring so many new men, he inadvertently handed an opportunity to the Communist-led Conference of Studio Unions. The swollen staff roster of 1941, much of it not around long enough to be enthralled with Walt, was a hidden danger; the numbers in union votes began shifting against him. Their Screen Cartoonists Guild narrowly won a bare plurality in the departments included in the vote. At 6 am on May 29, 1941, the picket lines went up at Disney.

Ink and Paint quotes Disney employees at length. Artist Grace Godino declared, “That strike was orchestrated by all the wrong people…It became vicious after a while, it became very bad”. Animation director Jack Kinney said “The strike became very bitter…the hostility was brutal. Strikers let air out of tires and scratched the cars as they drove through the gate. There were fights, even some shots were fired”.

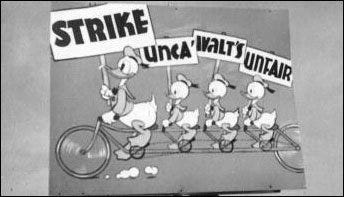

Walt Disney’s business interests were at stake, sure, but to an unusual degree he had created his own company, his own form of filmmaking—even moguls like Louis B. Mayer, David Selznick, Jack Warner and Harry Cohn didn’t do that—and he took the strike more personally than other Hollywood chiefs with labor problems. Disney had a stop-gap, low budget live action feature in theaters that summer, “The Reluctant Dragon”, a behind the scenes studio tour hosted by humorist Robert Benchley. CSU-sympathetic pickets went up at theaters around the country, with signs reading “The Reluctant Disney”, and Mickey Mouse was caricatured coast to coast. More than vandalized cars on Buena Vista Drive, that embittered Walt Disney; the notion that for the union, a mere internal studio dispute was worth dirtying the Disney name even for children.

He was shocked when even his young niece, a beginning animator, was cursed and spat at as she crossed the picket line. Walt Disney felt that men whose careers he created had betrayed him, and some had. The sense of violation stayed with him for decades. If the unquestionably Communist leadership of the CSU didn’t have an enemy before, they sure as hell had one now.

A postscript. By the Fifties the Cartoonists, like most other unions, had effectively erased their hard left past. Outside of the South, unions in general had reached mainstream acceptance in postwar America. Ordinary union members were among the millions of parents buying movie tickets and saving up for trips to Disneyland. Disney, the man and the company, never forgot what happened in 1941, but after a certain point it wasn’t in the financial interests of the company to stir up the past. Perhaps surprisingly, perhaps not, it didn’t seem in the interests of the animators either. Occasionally you’d see an older member speak up during the Vietnam and civil rights protests: “See! We used to march around with picket signs too!” The Disney strike was tacitly admitted to be a mistake, but it was supposedly disloyal to say so out loud. Better to forget it altogether.

In 1999, an excellent and comprehensive new history was published, “Hollywood Cartoons: American Animation in the Golden Age” by Michael Barrier. Like the tales of the talented, loyal ladies of Ink and Paint, it’s a fine contribution to telling a more complete Hollywood story. For the first time, the definitive history of American animation not only gently disputes many of the decades-old arguments of the strikers, but tentatively suggests—gasp!–that for once the boss might have a point, that an injustice was done to Disney. What’s more, the authority of the book won the day. Basically, almost every historian outside of the hardest core of old Marxists now admits that Barrier is right. He got people to admit what they always suspected about the cartoon factory’s fabled strike; so much of what we thought we knew about it was a fable.

To be sure Barrier gave the disappointed crowd just a little of the angle they hoped for, correctly stating the obvious: that most members of Communist-led unions were not, of course, necessarily Communists themselves. He also dutifully notes, rather irrelevantly, that as men making drawings and tracings of cartoon characters, they couldn’t have inserted Communist propaganda into Disney films. That’s something that not even the most angry of their enemies accused them of. It’s a bit of a “duh”, but trust me on this—even 48 years after the event, in the clubby world of writing film history, Michael Barrier took a chance with his book and even his career on behalf of telling a more complete truth. UNQUOTE- Gary McVey

Coming In Part 2: The Road To The Blacklist

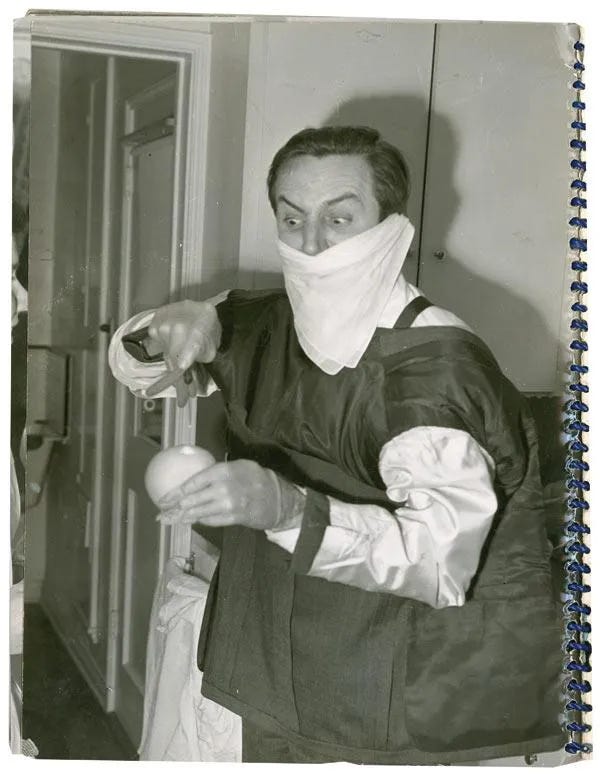

Behind the paywall: The Craziest Party Walt Disney Ever Threw

Disney at the party playing a mad scientist making drinks.

Walt threw a party for his employees and the booze was poured like water, employees awoke in each other’s beds, a horse took a dip in the pool! The most insane office party in history!

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Hidden Cold War History to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.